Podcast with Deavel and Wilson

/Notre Dame Center for Ethics and Culture podcasts with David Deavel and Jessica Hooten Wilson, editors of Solzhenitsyn and American Culture: The Russian Soul in the West, recently out from University of Notre Dame Press.

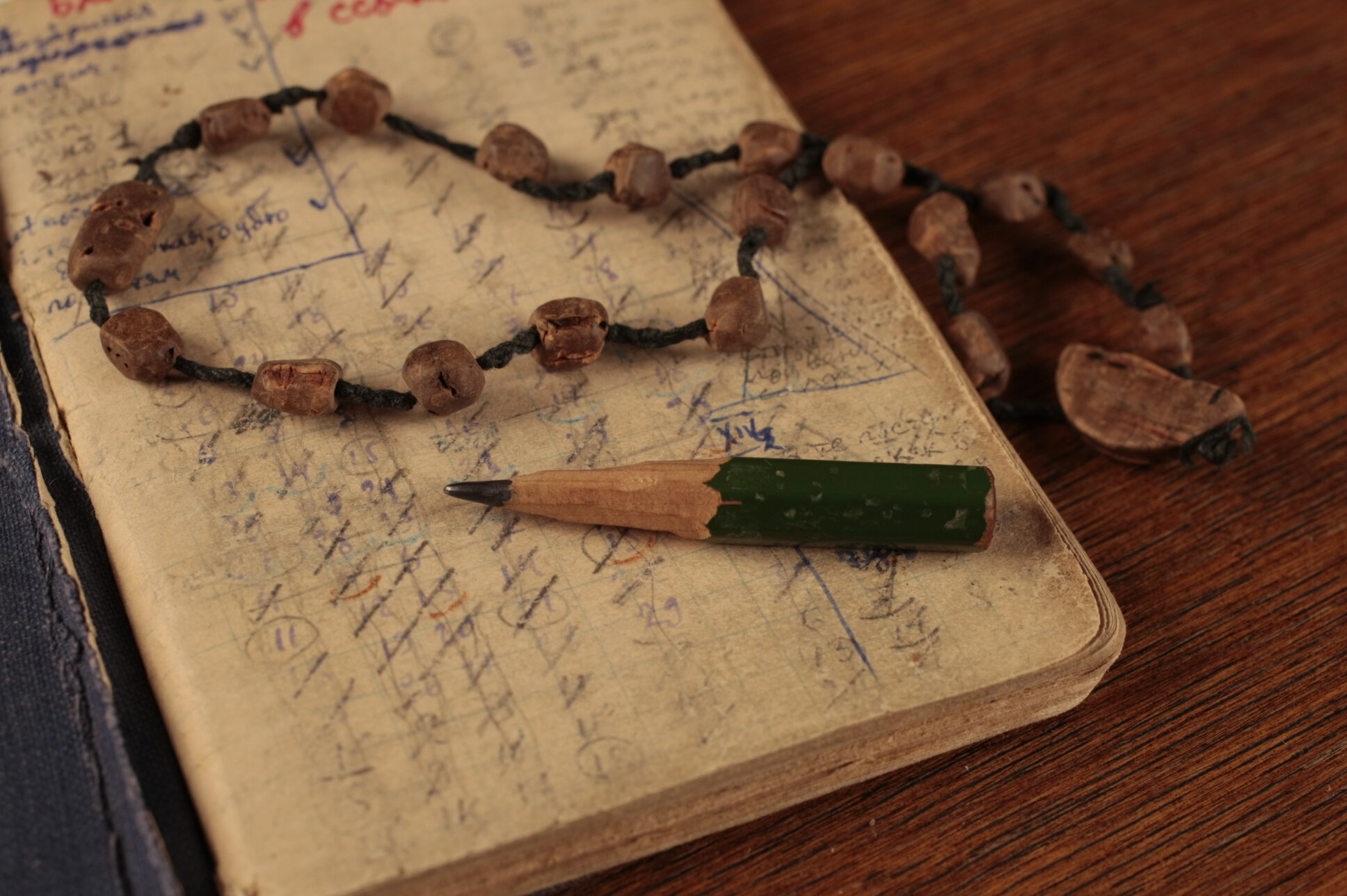

![10.11┆ “The man who is for the moment the most famous person in the western world” (C. Ogden) [=7.5].jpg](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5432c9c0e4b0d4b6148b3def/1609542526274-1IY3OTGP2WB00T8KWN6Q/10.11%E2%94%86++%E2%80%9CThe+man+who+is+for+the+moment+the+most+famous+person+in+the+western+world%E2%80%9D+%28C.+Ogden%29+%5B%3D7.5%5D.jpg)