Early Works > The Trail

The Trail

The Trail is an autobiographical poem of more than 7,000 lines published in Russian in 1999. Its author composed the poem between 1947 and 1952 under the worst of circumstances: as a prisoner of the Soviet state and without the benefit of pen and paper. As he composed the poem, he memorized it using techniques he has so unforgettably described in the third volume of The Gulag Archipelago. Utilizing a specially devised rosary as a mnemonic device, Solzhenitsyn was able to accumulate no fewer than 12,000 lines of verse during his time in a Special (Labor) Camp. This remarkable feat of memorization was a heroic effort on Solzhenitsyn’s part to hold on to those experiences that crucially shaped him in the six years leading up to his arrest and incarceration in February 1945.

The autobiographical main character Sergei Nerzhin begins his odyssey as a true believer of such intensity that he awakens early on each day of his honeymoon to read Karl Marx. Nerzhin’s rigid convictions largely blind him to the perversities of the ideological world that envelops the lives of every Soviet citizen. But in The Trail Solzhenitsyn mightily struggles to come to terms with his past. He forthrightly confronts those intimations of reality that somehow managed to break into his youthful world of illusions. In the opening chapter, Solzhenitsyn describes a canoe journey that he and a friend took along the Volga River in 1939. These two “Boys from the Moon” were oblivious to the evidence of inhuman forced labor and collectivization that was all around them. In the second chapter (“Honeymoon”), Nerzhin and his new bride come across a trainload of condemned zeks, an encounter that has a powerful, if temporary, impact on this committed Marxist. In later chapters, Solzhenitsyn describes encounters with Vlasovites, Russian soldiers who out of desperation and despair chose to fight with the dreaded German enemy rather than sustain a monstrous Soviet regime. Gradually these experiences left their cumulative mark on Solzhenitsyn/Nerzhin, although they did not lead to any immediate break with Sovietism. What Solzhenitsyn needed was a dramatic catalyst to open his eyes fully to the surreal world around him. This catalyst finally arrived in the form of his arrest at the front and his dazed return to Russia as a prisoner (events described in detail in chapters ten and eleven of The Trail).

Solzhenitsyn did not have the opportunity to write down the immense mass of The Trail until the summer of 1953, when he was in exile in Central Asia. His herculean efforts to confront his past, to defy his totalitarian masters through critical self-examination, and to preserve the memories that risked being lost forever can only compel admiration. The Trail describes the path of suffering and enlightenment that allowed Solzhenitsyn to become the mature and self-aware writer that we know.

– by Edward E. Ericson, Jr. and Daniel J. Mahoney, The Solzhenitsyn Reader

Selections from The Trail

Excerpt from The Trail, Chapter 9: Prussian Nights

…

Well, land industrious and proud,

Blaze and smoke and flame away.

Amid the violence of the crowd,

In my heart no vengeance calls.

I'll not fire one stick of kindling,

Yet I'll not quench your flaming halls.

Untouched I'll leave you. I'll be off

Like Pilate when he washed his hands.

Between us, there is Samsonov,¹

Between us many a cross there stands

Of whitened Russian bones.

For strange feelings rule my soul tonight.

I've known you now for all these years.

Yet, long ago, mere chance it was,

Mere caprice, that bound us tight.

Already, marching on Berlin,

Both anxious then and hopeful,

I'd look around—for fear we'd turn aside.

Long since, a premonition rose,

Ostpreussen! that our paths would cross.

Back home, beneath the dust of years

Secret archives hold unseen

What your arrogance thrust up

In the towers of Hohenstein.

I'm bound in duty to recall

How in '14, on this same soil,

By the same road our army takes,

This defile here between the lakes

—For Paris, the Miracle of the Marne—²

With bungling brain and blinder eyes

They drove them down, a six-day march

From their supports, from their supplies,

A knot of Russian Army Corps

Without reconnaissance, without bread,

To Ludendorff, beneath his feet;

And then, a blue sky overhead,

They drowned them there in the black peat.

And as he marched to their relief

Nechvolodov³ was recalled...

I nursed inside me till I filled

With muffled shouting, all the pain,

And all the shame, of that campaign.

In the dark cathedral gloom

Of one or another reading room

I shared with none my boyish grief,

I bent over the yellowed pages

Of those aging maps and plans,

Till little circles, dots, and arrows

Came alive beneath my hands,

Now as a fire fight in the marshes,

Now as a tumult in the night:

Thirst. Hunger. August. Heat.

—Now the wildly lunging muzzles

Of horses tearing at the rein,

Now broken units turned to raving

Mobs of men who'd gone insane...

1 General A. V. Samsonov, 1859-1914, commanded the Russian Second Army in the disastrous 1914 campaign.

2 The Russian invasion was designed to relieve the pressure on France; and in fact it led to a diversion of German troops, without which the French might well have failed to win the Battle of the Marne and save Paris.

3 A general in Samsonov's campaign.

---------------------------------------------------------------------

Excerpt from The Trail, Chapter 5: Besed

Rough, that bridgehead at Yurkovichi-Sherstin.

Many boys we left there in its wake,

Near its aspen saplings quickly felled,

Near its houses, laid to utter waste.

Mines would rip our only bridge, our only flimsy

Artery. . . .

Every day we straightened and attacked full-bore

Only to dank burrows to retreat.

In the dark of autumn night, cut off from our army,

We were beaten, pushed, and pressured into that black river—

Operation to expand the bridgehead!—

Who can understand your anguish and your fear?

All the land lies open, dead, disfigured, torn in craters . . .

All’s dug up, all, all that can be dug,

There’s no log, no stump, no rounded scrap of wood

To close up the trench, above your head.

Day and night they pound, they pound, they pound

Our human mass,

And not one stray missile will lie down and

Pass. . . .

Ashen, pallid faces in red clay;

Ground’s too wet—our shovels cannot shape it.

Trapped here! What a sorry, wretched piece of turf,

Little more than one square mile of earth.

We are pecked and pecked from planes above,

We’re cut down, cut down by heavy mortars,

When the sixes¹ hiss and hiss, the squeakers² bark and bark—

Hug the ground! These, too, are aimed at us! . . .

Day and night our sappers³ patch the bridge,

And our signalmen in water catch their cables

While the Germans pour it, pour it on the bridge,

And there trickles from the bridge a pinkish water. . . .

Once the lines are patched, then from the Mainland⁴

Pour and pour all cuss words known to man:

“Are ya stuck, ya

No-good mucking sacks?

Every single officer and every soldier

MUST! A!!—TTACK!!!”

1 Six: a six-barreled German mortar.

2 Squeaker: a heavy German mortar with a highly distinctive sound.

3 Sapper: A military engineer who specializes in sapping and other field fortification activities, or who lays, detects, and disarms mines.

4 Mainland: soldier slang for a land area temporarily secure from the enemy.

Additional Resources

Photo Gallery - 1942-53: Prison, War, Camp

Photo Gallery - 1954-56: Kazakhastan Exile

Available Formats

Russian Download

The Trail can be downloaded in the original Russian in PDF format at solzhenitsyn.ru.

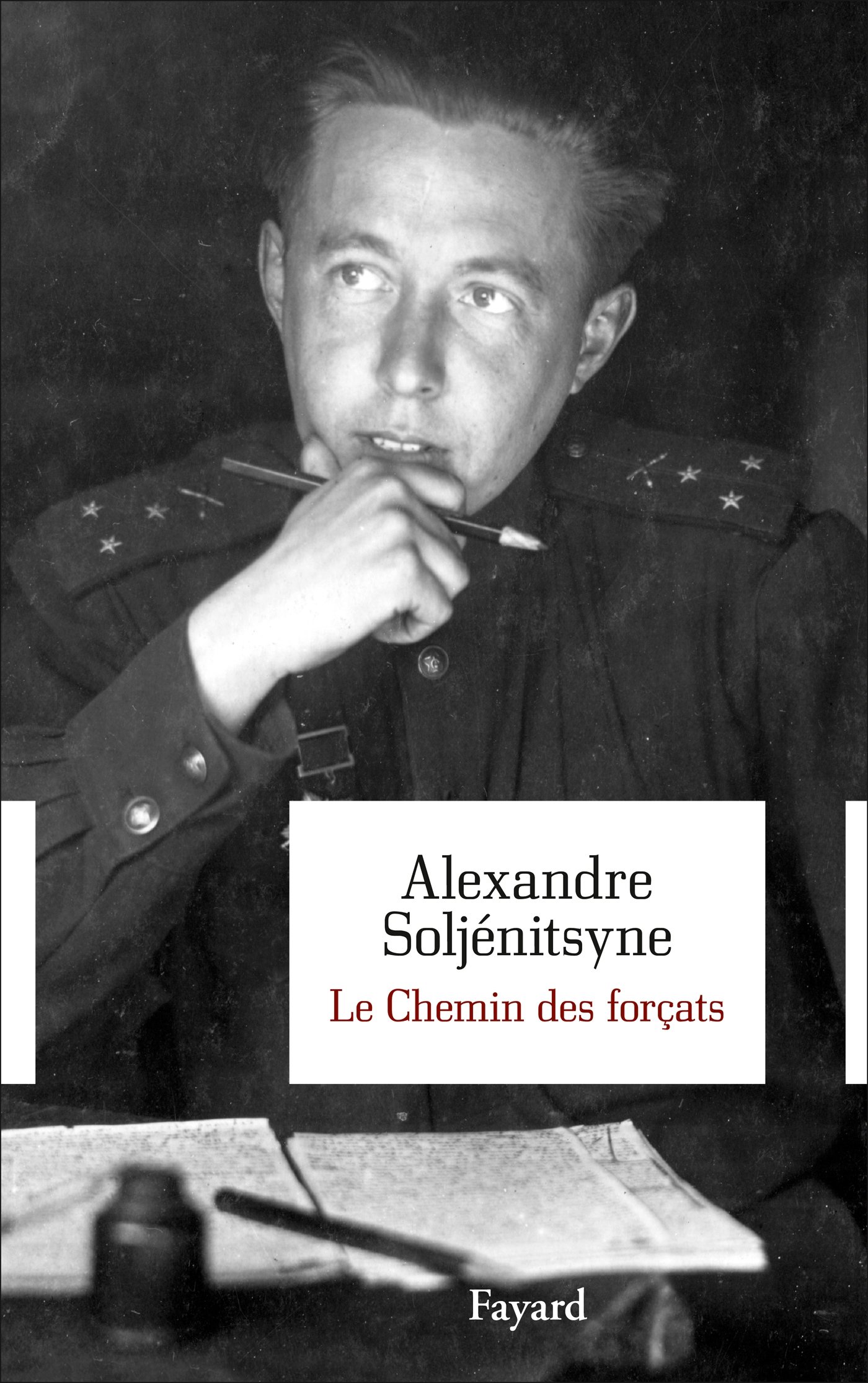

Le Chemin des forçats

French translation, 2014

Paperback

Amazon

E-book

Kindle

The Solzhenitsyn Reader

Includes "Chapter 5: Besed" from The Trail

Hardcover

Amazon

Paperback

Amazon | Barnes & Noble

The Trail, Chapter 9: Prussian Nights

This chapter was translated by Robert Conquest and published by FSG.

Paperback

Amazon